Finding Your Personal Investment Risk Tolerance

Deciding how to invest your money can feel overwhelming, especially when you see portfolios with labels like "moderate" or "moderately aggressive." They all come with different levels of risk and potential returns, but how do you know which one is right for you? The answer isn't found in a hot stock tip or a market forecast; it's found by looking inward. Effective investment management starts with a deep understanding of yourself.

Your ideal investment strategy sits at the intersection of three key areas: your willingness, your ability, and your need to take on risk. Getting this balance right is one of the most important steps in personal finance. Let's break down how to figure out where you stand on all three.

The Stomach Acid Test: Your Willingness to Take Risk

Investor Peter Lynch famously said, "It isn’t the head, but the stomach that determines your fate." This gets to the heart of the first and most crucial question you have to ask yourself: do you have the discipline to stick with your investment plan when things get rough?

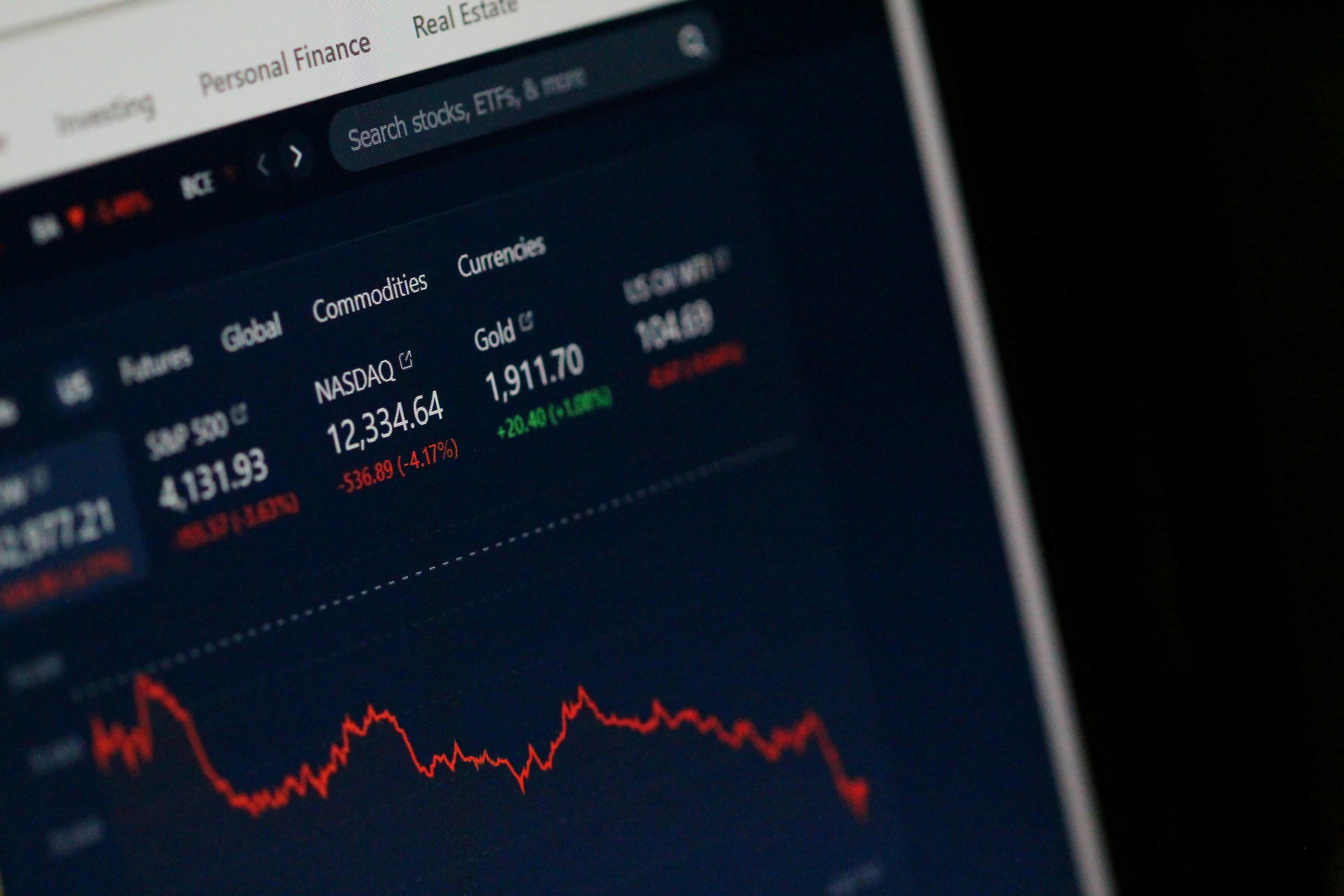

This is the "stomach acid test." It’s about gauging your emotional fortitude. Successful investing depends less on genius insights and more on your ability to handle stress during the inevitable downturns in the financial markets. To see how much of a gut punch you can really take, consider what it would have felt like to navigate the bear markets of 1973-74 or 2000-02.

To achieve the higher returns of more aggressive portfolios during those times, you wouldn't just have to stomach a nearly 40% cumulative drop; you would have needed the courage to buy more stocks to rebalance your portfolio when it felt like the sky was falling.

Let’s walk through what that actually looks like. Imagine you have $100,000 in a moderately aggressive portfolio with an 80/20 split: $80,000 in stocks and $20,000 in fixed income. The market tanks, and your stocks lose 40% of their value. Your $80,000 in equities is now worth just $48,000. Your total portfolio value has shrunk to $68,000.

To maintain your 80% stock allocation, you now need your equity position to be $54,400 (80% of $68,000). That means you have to sell $6,400 of your stable fixed-income assets and use that cash to buy more stocks—right in the middle of a market collapse. It takes incredible discipline to buy when everyone else is panicking, but that's precisely what's required to capture the long-term returns of a riskier strategy.

So, look in the mirror and be honest. Could you sleep at night after watching your portfolio lose over 24% in a single year, followed by another painful year, resulting in a cumulative loss of almost 40%? If you overestimate your tolerance for pain, you might panic and sell at the worst possible moment, locking in your losses. In that case, you would have been far better off with a more conservative portfolio from the start.

If the answer is "no," simply move to a less aggressive portfolio and repeat the question until you find a level of risk you can genuinely live with. This isn't just theory; it's a practical economic theory application for your own life. You can use this table as a rough guide to match your maximum tolerable loss to an equity exposure you might be comfortable with.

Ultimately, you're choosing between sleeping well and eating well. A conservative portfolio helps you sleep well by minimizing volatility, but historically, it has meant leaving significant potential gains on the table. There's no single right answer, but understanding the consequences of your choice is critical.

Your Ability to Take Risk: More Than Just a Feeling

Your emotional tolerance is only part of the equation. Your practical ability to take on risk is determined by more concrete factors: your investment horizon, the stability of your income, and your need for liquid cash.

First, your investment horizon is key. The longer you have until you need the money, the more time you have to recover from the market’s inevitable slumps. Someone investing for retirement in 20 years has a much greater ability to take on equity risk than someone saving for a down payment in three years.

Here’s a guideline for thinking about your timeline:

Second, think about your income stability. A tenured professor with a steady paycheck has a higher ability to take risks than an entrepreneur whose income fluctuates or a factory worker in a cyclical industry. The more stable your earned income, the more you can rely on it to cover expenses during a market downturn without having to sell investments at a loss.

Finally, there’s the liquidity test. Before you invest in anything long-term, you need a cash reserve for emergencies. Financial planners typically recommend setting aside about six months of living expenses in a safe, easily accessible account like a money market fund or high-yield savings. If your monthly expenses are $5,000, you should have a $30,000 emergency fund built before you start investing in stocks or long-term bonds.

You also need to set aside funds for any known, near-term expenses like buying a car or paying for college tuition. This money should not be exposed to significant market risk. For instance, if you need $30,000 for a new car in three years, that money should be in fixed-income assets. The equity allocation for that specific goal is zero, based on the investment horizon table.

A strong liquidity plan does more than just prepare you for emergencies; it gives you the confidence to ride out market volatility. Knowing you have your short-term needs covered makes it much easier to stay disciplined with your long-term investments.

The Need to Take Risk: Aligning Your Goals with Reality

The final piece of the puzzle is your need to take risk, which is driven by your financial goals. What rate of return do you need to achieve your objectives, like retiring at a certain age or leaving an inheritance? This is an often-overlooked part of investment management.

The higher your financial goal, the more risk you generally need to take. But this is where you have to consider what economists call the "marginal utility of wealth." In simpler terms: how much is that extra dollar really worth to you? At some point, most people reach a lifestyle they are comfortable with. Beyond that point, the stress of taking on more risk for a potentially higher net worth just isn't worth it. The potential downside of a bad outcome far outweighs the benefit of a little more wealth. This is a crucial concept in personal finance, as it helps prevent wealthy investors from taking unnecessary risks.

If the rate of return required to meet your goal is higher than your willingness or ability to take risk allows, you have a few choices:

- Lower your goal: Accept a more modest retirement lifestyle.

- Save more now: Reduce your current spending to lower the rate of return you need.

- Accept more risk: If the potential reward is truly worth it to you.

Your required rate of return will help determine your ideal equity allocation. While this depends on current financial markets, the following table offers a reasonable guideline for what it might take to achieve certain returns with a passive investment strategy.

Building Your Portfolio: Putting It All Together

Once you've analyzed your willingness, ability, and need, you can determine your overall asset allocation. The rule of thumb is simple: your final equity allocation should be the lowest of the outcomes from these three tests.

For example, if your stomach acid test says you can handle a 70% equity portfolio, but your investment horizon (ability) suggests a maximum of 50%, then your upper limit for equities should be 50%. The most conservative number should always win. This is a straightforward economic theory application designed to keep you from taking on more risk than you can handle, either emotionally or practically.

This entire process should be formalized in a written Investment Policy Statement (IPS). This document is your business plan for investing. It should be reviewed annually, or whenever your personal circumstances change dramatically, to ensure it still aligns with your life.